Adrian Duke showed me his phone while we stood outside Vancouver's Skwachàys Lodge. An animated raven popped up to tell me the story behind this boutique hotel, which houses Indigenous artists and their works. The raven was modelled on a commissioned painting by Garnet Tobacco, whose other paintings are on display inside the gallery.

Skwachàys Lodge used to just be another hotel until the nonprofit Vancouver Native Housing Society took it over, in 2011. Squamish Nation Chief Ian Campbell named it after the once-marshy land it occupies. Now, it houses Indigenous artists-in-residence, those at risk of homelessness who are given shelter-rate apartments, and patients who come from elsewhere in British Columbia, on Canada's West coast, seeking medical treatment in this city.

Duke, 30, is a member of the Muscowpetung Nation. He's developing a new augmented reality app—think Pokémon Go—to share Indigenous stories that are tied to physical places like this one. It's called Wikiupedia, and Skwachàys is one of its first geolocations.

The models for Wikiupedia's animal avatars were painted by artists in residence at Skwachàys Lodge. Image: Megan Devlin

"The app is another way that just allows people to access traditional knowledge that isn't really readily available," he told me. "You might not have the ability to chat with elders or hear some of these stories," but the app allows users to experience the Indigenous history of their city. The name is a play on wickiup, a small round tent, said Duke.

Wikiupedia moved into beta this week, and Duke is working on fixing bugs as well as populating it with stories. Just like Wikipedia, stories on the app are crowdsourced. Right now there are six stories, all in downtown Vancouver. Duke wants to have 600 from across Canada in time for the app's public release, in June. He sees it growing to become a digital Indigenous knowledge network.

Read More: This Aboriginal Keyboard App Is Helping Preserve Indigenous Languages

Duke's project received funding from the federal government's Department of Canadian Heritage, which is pushing Canada's 150th anniversary this year. He says about $200,000 went into developing the app.

David Gaertner, an expert in digital storytelling with the University of British Columbia's First Nations and Indigenous Studies program, told me that he loves the idea.

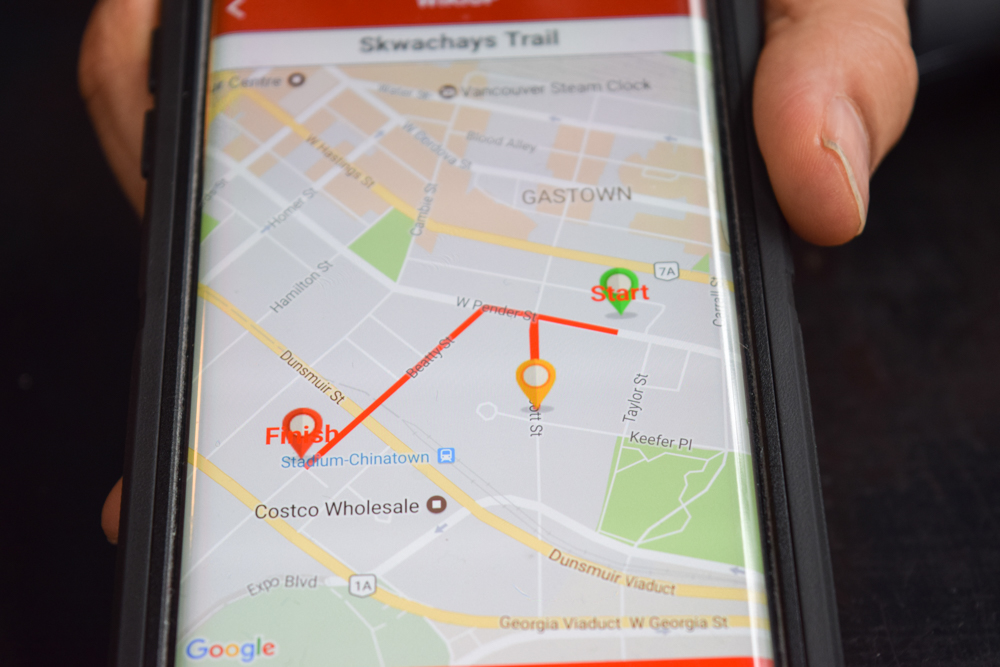

Wikiupedia ties Indigenous stories to physical markers on a GPS map. Users can follow trails of markers strung together to reveal their significance. Image: Megan Devlin

"Augmented reality brings those connections between land and story back into relief in new and exciting ways," he said. "I think [Duke is] taking advantage of a technology that can do some real good about unsettling our colonial interpretations of place."

Canada has over 600 First Nations, and that's not including Métis and Inuit people. That means a lot of stories.

Duke has connected to Indigenous housing associations across Canada. Their job is to motivate youth to submit stories. Every successful story tied to a geographic marker will earn the creator $50.

They've also got a community vetting process.

"There are a few different authentication layers," Duke explained. "If I was to post a story from my region, it doesn't necessarily mean that I have to be of that nation, but in that region we have cultural authenticators."

Duke says they're planning on replacing Google Maps' default markers with customized ones by Indigenous artists in each region of Canada. Image: Megan Devlin

In other words, cultural knowledge-holders vet each story for accuracy before it's posted.

"Ultimately the biggest challenge is making it as accurate as possible without putting too many barriers in front of people," Duke said.

Gaertner said that Indigenous artists re-layering stories on the land is not new.

He points to Quelemia Sparrow's piece "Ashes on the Water." The Musqueam artist created a podplay—similar to a podcast—that tells the story of two women on either side of the Burrard Inlet during the Vancouver fire in 1886. It's set a century ago, but you're supposed to envision the story while standing on the same beach in the present-day downtown.

"We're not being asked to step through the frame and into the art, we're being asked to experience the land around us in different ways," Gaertner said.

"For me, something like The Survivors Speak series that came out of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is a really powerful example of the role that storytelling plays," Gaertner said.

He was referring to the transcripts from residential school survivors that came out along with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's report in 2015.

"I think there is just something inherently powerful about people speaking from their own experiences in their own words," Gaertner said.

Duke hopes his app could foster reconciliation through storytelling.

"Reconciliation can only happen if somebody is interested in actually learning and being a part of that conversation. And so I think engagement and awareness of the culture in general is really the first step."

He hopes that Wikiupedia can preserve Indigenous culture.

"We're losing our languages and we're losing our stories along with all the elders as they go," he said. "I think, for me, that's the most important reason."

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter